A Biography of Robert Granville Caldwell, Jr.

Part I – Spy Catcher

A Biography of Robert Granville Caldwell, Jr.

Part I – Spy Catcher

By Duncan Caldwell

with important contributions from David, Susanna and Nicholas Linfield

© 2009 Duncan Caldwell

My deep thanks to my nephew, David, who interviewed his grandfather and caught his vernacular. Much of the following history of my father’s life could not have been written without those interviews. I am further indebted to my sister Susanna, who enriched the original interviews with extra details and rich memories while transcribing the tapes, and to my brother-in-law, Nicholas, who typed her manuscript. The three of you will find that this narrative strays at moments from your work, because it melds words and details from multiple tellings, including ones I remember my father telling me over the years. My thanks to you all – and most especially to him.

The Youth of a Reluctant Warrior

My father, Robert Granville Caldwell, Jr., died on April 4, 2009 - exactly 22 years after my mother, Ruth. He had been counting down the days to the anniversary, and suddenly asked, when he was partially paralyzed by a stroke, strapped to his bed, and, seemingly, without much remaining control over his life, “I wonder if I’m doing the right thing.” Although he lived such an eventful life as a reluctant soldier and circumspect intelligence officer, I hope the following stories will show how sensitive he was to the moral quandaries of a life deeply embedded in the history of our time. Part I of this meditation on events that awed and haunted him covers incidents until the end of World War II. I hope to tell the still richer compendium of stories of what happened next in Part II.

Robert, or Bob as he was called by most people, was delivered into this world by a country doctor using forceps in his maternal grandfather’s house in Columbus Grove, Ohio on August 24th, 1917. “The doctor had a horrible time getting me out and I still have a depression in my skull. I blame everything on that,” my Dad once recalled with a chuckle. “My mother told me years later that I was the ugliest baby she had ever seen, and that made a big impression on me.”

Bob also remembered visiting relatives back in Ohio and Connecticut. Sundays with his pious Presbyterian grandparents in rural Ohio were so quiet and stifling, that they all but cured him of religion. Then on August 2, 1923, when my Dad was almost six, he awoke to politics when one of his grandfathers, who was sitting on the porch listening to the radio, heard that President Harding had died, and quipped: “The Volstead Act and giving up the drink must have been too much for him!” Such irreverence and iconoclasm insinuated themselves into Bob’s opinions until they even leavened his views of presidents he knew personally.

Another time, he and his two sisters, Alice and Janet, who bracketed him in age, were playing farm in the garden, when his grandmother called jocularly, “Bobbie, stop milking your sisters!” – instantly transforming innocence into experience and making the memory stick forever.

Columbus Grove, Ohio in 1923 or ’24. Left to right: Janet Caldwell, Lillian Thomas, Alice Caldwell, Bob Caldwell, & Edith Caldwell holding Edith Kunneke.

Around this time, the family stopped taking the train north from Texas because five full fares were too expensive. Instead, my grandfather, Robert senior, would drive them to his parents-in-laws’ - the Jones’s - farm in northwest Ohio and then drive on to New York to teach summer school at Columbia. The attic and basement of the farmhouse contained a hoard of mortuary pots and other grave-goods that Bob’s Grandfather Jones had collected from mounds in Arkansas while logging there in his youth. The artifacts fascinated Bobby – continuing an interest for antiquities which has grown in our family ever since, leading, in my case, for example, to peer-reviewed work on Neanderthals and paleolithic feminine imagery. No effort was made to preserve the trove as Bob’s grandmother filled one pot after the other, over the years, with water and sat them on radiators to humidify the house – a practice that was supposedly invigorating. Being low-fired, they each disintegrated because of this ill treatment, leaving us descendants with just two simple jars, a wondrous Canada Goose figural bowl, and a great deal of regret.

One summer, while rummaging in the hoard, Bob even found a pot with a skull inside. When he brought it into the house proper, it caused consternation and his grandmother ordered her husband to hide the skull away from the children. But the next summer, Bob found the inappropriate momento concealed in the back garage and brought it back into the house. This time it disappeared for good, probably buried by Grandpa Jones back in the cornfield.

One of Bob’s first memories from a stay with another branch of the family remained among his most traumatic – even after years of battles and terrorism: his extended family had united at his uncle and aunt’s home in Ridgefield, Connecticut and were having a backyard fireworks display for the fourth of July when a Roman candle spewed sparks into his cousin’s dress. The children’s eyes were wells as they watched her father desperately wrap her blazing and writhing body in blankets to snuff the flames – only to fail to save her. Although Bob would live to 91, such accidents, three landings in WW II, civil wars and invasions would mark him with life’s precariousness. But he never abandoned the conviction that moral decisions pattern life more deeply than hazard.

Back in Houston, the next door neighbor collected derelict circus animals and the garage below Bob’s bedroom was filled with emaciated animals peering from narrow cages. He often fell asleep to the whimper and roar of a mangy lion turning on its own length through the nights. Once the man even obtained a raw pachyderm hide from an elephant that had died at the zoo and pegged it over his lawn, so he could scrape off the meat. Then, at 12 - in an age when there was no such thing as a driver’s license - Harris and Bob took the family’s Ford across the city to the beach. As Bob drove - freckled, skinny and with his head barely above the steering wheel - through a stretch of low houses, a woman ran screaming from her house onto the stage of her porch, pursued by a large man, who slashed her throat with an open razor. Bob never told his parents of the horror.

Columbus Grove, Ohio in 1928. Left to right: Edith Kunneke, John Kunneke, Janet Caldwell, Alice Caldwell & Bob Caldwell

My father’s own father was a contemplative historian, thoughtfully puffing his pipe as he wrote reflective biographies of two assassinated Presidents, Garfield and McKinley, as well as a two-volume history of Britain’s American colonies and the United States which has stood the test of time, because hardly a page seems ideologically or methodologically dated, even as histories incorporating more recent decades have supplanted it. Caldwell senior had been born in the Andes and after earning his doctorate had gone to teach for two years at a college for Indians - in India. As a young man, he had also been active in the Halfway House program linked with Norman Thomas’s Socialist Party.

Bob’s parents, Robert G. Caldwell, Sr. & Edith Caldwell

Now in the midst of the Depression and job insecurity, my grandfather, Robert senior, had risen to be head of the History Department, Dean of Men and general gofer for the President of Rice Institute. But he had been disappointed when some of his colleagues, even good friends, got offers from other universities, and then parlayed them into raises, after he had received similar offers, including one to become President of his alma mater, Wooster College, but had stayed at Rice out of loyalty. As a result of this sentimental failure to leverage his position, his salary had fallen far behind those of his peers, who were now earning over $10,000 a year while his salary was stuck at less than $7,000.

So he was all the more open to a career-change, when he was suddenly offered the equivalent of an ambassadorship. It happened in the most indirect fashion. My grandfather’s brother, Bill Caldwell, was the most prominent obstetrician in New York, having invented a method for measuring pregnancies, which would be used worldwide until the invention of ultra-sound, and had befriended a wealthy stockbroker named Ben Smith after being his wife’s doctor. Now it so happened that Mr. Smith had contributed heavily to F.D.R.’s campaign in 1932 and was offered the equivalent of an ambassadorship to Portugal. Since Portugal was no longer a “Great Power”, America kept a legation there led by a “minister” rather than an “ambassador”. Smith thought he had better things to do and recommended his friend Bill, the obstetrician, for the post instead. But Bill deferred too and recommended his brother, the American historian. Given the times and consequences, I would have to say that the best candidate got the job in the end.

There were two catches though: America still could not afford to pay for the pomp of the great European powers, so diplomats were expected to finance lavish receptions on their own - which gave presidents all the more reason to choose wealthy contributors. The only problem was that Robert senior was anything but wealthy, so money became tight.

The second catch was that it was 1933. Bob and his two sisters were being sent to Portugal alone in an old liner to join their parents, who had gone ahead, when the radio announced that the Spanish Civil War had broken out – just as the ship was caught in a gigantic hurricane! Amid tumultuous seas, the Spanish crew mutinied, declaring their allegiance to Communism and forced the seasick children to listen to revolutionary lectures with other passengers. The armed men shouting in the lurching leaking hall stayed with Bob like a surreal nightmare. Finally, the crew relented, though, and delivered their charges to Lisbon. It was a foretaste of decades spent in the tempest of ideological passions and delusions blowing from both sides of the Cold War.

But then the family was separated again. French being the lingua franca of the time, it was decided that Bob and his sisters would attend a tiny boarding school in Grenoble where they would be immersed in French for a year even as their mother, Edith, took lodgings nearby in case of need. Bob rankled under the stern foreign educational system and never became fully fluent, but this exposure to French would soon shape his life. The next year, he was sent to live with the Humphreys - family friends in Winneteka, Illinois, where he went to New Trier High School for what were supposed to be his last two years of secondary school.

Jim Thorpe, the Native American super-athlete, whose Olympic gold medals had been taken from him on the charge that he had once accepted a small amount to play baseball, visited the school and gave Bob the only autograph he ever treasured – in part because Dad suspected, like many people, that Thorpe had been penalized mainly because of his ancestry.

Bob in Winnetka, Illinois in 1934.

Bob savored the reversal but never exacted retribution.

Before that, however, Bob went to Yale from 1936 to 1940 – and, after 4 years in Portugal, his parents moved to the Andes, where Bob’s father had been born and now became American Minister to Bolivia. In the midst of Bob’s college years, which were filled with camaraderie, he sailed to France on its greatest liner, the Normandie, for the summer after his junior year. He bicycled along the Loire, sketching chateaux and cathedrals and staying with local families to improve his French.

Then, on September 1, 1939, Germany and the U.S.S.R. invaded Poland and Bob’s idyll was over. His parents, who were now living in Belmont, Massachusetts after Robert Sr. had been named Dean of Humanities at M.I.T., telegrammed and summoned their son home. Bob took the Normandie back on what would turn out to be her last voyage, since the war stranded the ship in New York, where she was blown up by saboteurs trying to prevent her from being converted into a vast troopship for bringing American soldiers to Europe. My Dad looked back upon her with awe: I suspect that she had come to symbolize all the grandeur, grace and common good which tyrants are so willing to destroy to achieve their ends.

After graduating from Yale, Bob went to an ad hoc preparatory course for future diplomats in Washington called the Foreign Service School. But he knew it was almost certainly only a matter of weeks before he was drafted into the military at one of its lowest ranks unless he quickly volunteered or got special training, so he tried to get into a naval officer training service called the V-12 Navy College Training Program. They didn’t accept him. Then, while he was in New York City trying to get into V-12 in early 1941, the first draft was decreed. He had to register immediately – and did so in a school on the East Side.

Bob in Washington, D.C. after college in late 1940

Around the same day, the head of Standard Oil of New Jersey, who was one of his uncle Bill’s acquaintances, offered Bob a job in Venezuela if he could get a six-month deferment. Bob was carrying his draft registration receipt during a short visit back to see his parents in Belmont, when he was summoned by the local draft board. This board said his New York registration number didn’t appear in its system and promised Bob that it would give him a six-month deferment, if he would only re-register, so the local board’s system could generate a number of its own. He bought the lie and re-registered and they had him in the Army the next day. He would suspect and chafe under authorities, even when he worked for them, for the rest of his life.

“You know,” he explained, “I was ready to serve; I had already tried to go to officers’ school.” Soon Bob was undergoing excruciating training for the country’s first amphibious landing along with thousands of other privates in the swamps of Camp Edwards. When traveling to and from Martha’s Vineyard in later years, he would often point out a house and a sand-trap on the golf course in Woods Hole with bittersweet nostalgia because he had spent his furloughs with a young lady there and evenings snuggling and hoping with her in that bunker. After a while, he and others became Privates First Class. Then he was sent on maneuvers in the Carolinas around Fort Bragg with the 101st Eighty-First Infantry Regiment of the Yankee Division – and was spotted by one of the umpires of the military “games” who advised him to apply for the C.I.C., short for the Counter-Intelligence Corps.

Instead Bob applied for infantry officers’ training and was accepted, only to have his orders superceded by the C.I.C. at the last moment. He was instructed to report to spy school in Chicago at once. The umpire must have fingered him.

By then Bob was a sergeant and went to counter-intelligence school in back of the old water tower on Michigan Avenue. “We learned all the trade craft of the period,” he recalled, “placing mikes, learning to tail suspects, the works.” After graduating, he was promoted yet again and eventually sent off to Maine, where he was put in charge of military counter-intelligence for the entire state. He was supposed to liaise with the FBI all the same, even though the FBI looked down on the C.I.C. youngsters as neophytes and sent them on wild goose chases. Every time “little old ladies” reported any lights blinking off the coast, the FBI passed him the job of interviewing them.

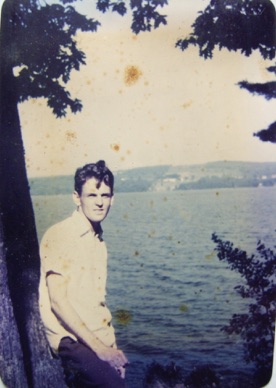

Robert Caldwell in Maine as the chief C.I.C. investigator. 1941.

Another time, the air force asked the C.I.C. to investigate suspected sabotage because a surprising number of planes had been damaged at bases in the extreme north from which planes were flown to England. “So,” my father once recalled, “we drove way up to these big airfields, Presque Isle and Houlton, near Nova Scotia and began to interview people connected with these wrecks and it turned out, in every case, that it was just pilot error. These kids were just out of college and were flying planes to Europe with hardly any training. One just pulled up his landing gear while he was still sitting on the runway - and the plane dropped from under him – breaking it in two. The rest of the cases were similar. There were no spies. It was just bad training.” The twin themes of false assumptions and blundering became ones which Bob would expose and inveigh against repeatedly, culminating in cables from Saigon in the early Sixties against sending a large land army to Viet Nam. But, in the summer of 41, that was a long way off.

Suddenly he got orders to report for more overseas landing and combat training. As a senior sergeant in the C.I.C., he was assigned a large platoon of mostly well educated men – including the guy who had hazed him at Andover and another man, named Parish, who had gotten his doctorate under Bob’s father at Rice Institute. Although they weren’t infantry, they were to be trained exactly the same as all the other soldiers, climbing down walls with netting to simulate climbing down cargo nets on ships. But Bob already had infantry training, so he became a trainer, putting his charges through their paces from the rifle range to obstacle courses under simulated fire. In October they left Fort Dix for Camp Picket and boarded the Tasker H. Bliss - a former Pacific liner that had been known as the President Cleveland.

The S.S. President Cleveland was renamed the U.S.S. Tasker H. Bliss before sailing across the Atlantic as a troopship.

“Even though our platoon was part of Patton’s headquarters contingent - he wasn’t on our vessel, but we were sure under him,” Bob once recalled, “we had to sleep four to a sack right next to the ‘shaft alley’ where the giant shafts were turning the propellers. The machinery was right next to our shoulders and I had a second-tier bunk in which I couldn’t turn over without hitting the bunk on top of me - it was so close. We had regular exercises running up and down cargo nets from one end of the boat to the other with lots of men. Weeks went by as we sailed way down south off South America and then across to Dakar, trying to evade and fool the German submarines. I learned later that the idea was to make the Germans believe we were going to attack Senegal, which was under Vichy control. Instead, the fleet suddenly sailed north on the night of November 7th, 1942. At a midnight breakfast before the landing, I was shocked at how many men pushed in front of other soldiers in line. Even though some of us were bound to die in the morning, some people just couldn’t be civil.”

The invasion fleet as it crossed the South Atlantic towards Fedala.

In the twilight before dawn, the converted liners and other troopships were looming off Fedala on the rough Atlantic coast of Morocco. Enemy subs had been trying to find the lumbering troopships all the way across the ocean and American destroyers were now maneuvering incessantly to try keeping them out of the flock as the battleship Texas and Cruiser Brooklyn lobbed shells at the French battleship Jean Bart and three batteries at the top of a cliff in Fedala. The American soldiers milling on the decks, waiting for their turn to scramble down the cargo nets, could see the shells crossing the sky and landing on the fortress. It seemed only a matter of time before Nazi subs found the huge ships badgered by their litters of landing craft – as indeed it was – the Bliss later going down with hundreds still aboard – so the only refuge seemed to be the craft lurching below.

“I scrambled down the cargo net,” my father recalled, “I was with three others and a major named Ellis who was in charge of our unit. He had served in World War I and was out to win medals. One of the guys climbing down into the landing-craft (which I think had only one vehicle in it) was the naval ensign who was supposed to drive the boat. The thing I remember most about crawling down that net was the overwhelming stench of excrement and getting it all over my hands. Soldiers were literally scared shitless.”

With their faces in the ropes, the swarms of men tried to cling long enough to the slippery webbing to have a chance of leaping into landing craft as surges lifted and crashed the craft spasmodically against the hull’s cliff, often crushing the legs of lower soldiers who tumbled, screaming into the sloshing sea as the ships lurched apart. Because of America’s utter lack of experience in landings, everyone was overladen, and even uninjured men couldn’t swim under their load of guns, grenades and ammunition.

“The Major had loaded them down,” Dad remembered. “Every one of us was loaded with three different arms: a .38 police special pistol, Thompson submachine gun, and M1 Garand rifle, plus dozens of pounds of ammunition. We were heavy as caskets.”

After pitching towards the beach squeezed in the cell under the yawing sky, the ensign at the helm of the small landing craft found that he’d gotten lost in the spray, smoke and melee, so, by the time the boat arrived at its assigned landing slot in the surf and the bow ramp dropped, they could see other troops landing. The first assault wave, which Bob’s group was supposed to have been in, was taking the heaviest casualties. Tracer bullets and other gunfire was zipping everywhere. To make things worse, the craft’s still primitive design had caused it to run aground in water that was still over a man’s head, so the first overladen soldier to jump was simply swallowed in spume and drowned. As everyone began to jettison extra grenades and ammunition – things they knew they might need soon - huge waves surged over them, tipping the deck.

There were so many troops and landing craft in the surf, that we couldn’t maneuver - there was hardly any place to go. Hundreds of boats had overturned because of poor design. Then ours capsized, throwing us all into the sea. How we managed to scramble ashore, I don’t know. Then, when we looked back, the ensign was obviously drowning in the roiling surf, so we all went back in the water and pulled him out. Hundreds of men did drown along that beach that day.

No sooner had we gotten this guy ashore, than American-made Curtis airplanes that we had sold to the French began to strafe us, and I leapt in a foxhole that I found occupied by an American killed in the first wave - fell right on top of him. He was the first person I saw killed by enemy fire and I must say it was very impressive. I was impressed mostly by how gray dead people look and how quickly they look gray.

In another telling, my father told how he once slid for a foxhole at the same time as another guy – only to arrive earlier and to have the other soldier go limp on his back as he took a bullet which would otherwise have claimed my dad-to-be.

As Bob and the other surviving American soldiers crawled and scrambled from the surf, they each wore a colorful Star-and-Stripes armband, which was meant to inform the defending French forces that their traditional American allies had come as liberators and, most importantly, to differentiate Americans from the English, who most Frenchmen reflexively suspected of taking advantage of France’s weakness to try stripping her of colonies. The bright armbands were to no avail – except that they were as blatant as redcoats – as the Vichy planes, machine-guns and artillery from Fort Fedala pounded the sand.

Next came friendly fire. Here’s how Bob remembered it:

I got up nearer the town - a bit to the south of where we landed - and the Texas, Brooklyn and some destroyers just kept firing at the Vichy guns at the top of the cliff. Since it was a low trajectory, if they didn’t hit the batteries, the shells just sailed over the enemy fortifications back into Fedala where they dropped amongst us as we got into the town. The next day, after the French guns were finally taken from the land side and silenced by the army, I saw a violent argument between the senior naval officer, who had come ashore, and the commander of the troops who had landed and had repeatedly been in a position to take the fortress from the rear, with hardly anything in the way, when the navy had begun firing again. The army general was furious that the Navy had kept firing and landing shells among his troops after repeated high level requests to stop. But the admiral was a stickler for procedures and said that as long as anyone fired at his ships, they had the obligation to respond – that was all there was to it. There was absolutely no willingness to coordinate with the army or even avoid feeding into enemy tactics.

The same kind of thing happened at Port Lyautey along the coast toward Tangier. Our soldiers were driven off three times over several days by the same kind of thinking: if there was anything coming out from the land towards the navy, they kept firing. At Port Lyautey, it drove our troops back from positions they had even captured. Friendly fire was one of our worst enemies. Maybe things got better later: this was just the second landing of the war, coming just a few months after Guadalcanal - and the first in the Atlantic theater, but it made me even more wary of bureaucracies – even the ones I worked for - and their self-righteousness. That certainly was a dramatic time for me – the first of many in battle.

Horribly, the carnage was almost prevented – except for a tiny blunder. The Office of Strategic Services or O.S.S., as it was called, had almost flawlessly executed a plan with so-called “control vice-consuls” to keep the Vichy French from resisting the invasion. These agents were posted everywhere that seemed important for the invasion. Some had successfully entered Morocco under State Department cover and even recruited General Béthouart and other conspirators to arrest the top Vichy commander, General Noguès. It went off perfectly – except that, after they arrested him on the night of November 7th, the agents left Noguès alone in the confinement of his office with his telephone, which he used to order resistance to both the coup and landings. As a result, it took three days for the Americans to take their initial targets, Fedala, Safi, and Port Lyautey.

After the battle, Major Ellis, who had ordered the men to carry so much into the surf, called several together, “This is the time, you know, to get medals,” Ellis announced, “but we can’t all get them, so, if we have to choose anybody, my choice is Jim Furness.” Jim, who had already become the Major’s favorite before the landing, had been in the landing craft right behind Bob’s and had just graduated in the Yale class after him. “So, what I’d like to know,” the major continued, “is would the rest of you write up an affidavit telling how he risked his life to save the ensign?” Jim had participated in the rescue, so nobody saw any reason to deny him a citation that they knew most of them deserved. Here’s my father again, pondering a growing sense of entrapment:

There were a bunch of us there - one was Miguel Ignacio Carranza, a Mexican-American – and Jim seemed as deserving as anyone, so we wrote it up for him. And then as soon as the guys decided to give the second-highest honor they could recommend for Furness, the Silver Star, Major Ellis said he thought he deserved one too, and insisted we write him up - and I don’t know why we knuckled under to him, since Carranza and I were very upset. But, we succumbed anyway, and wrote up something, so after warming us up, Ellis rode Furness’s coattails and got his medal too. That made me very cynical about medals from then on.

As the head of the C.I.C. platoon, my father’s next target was nothing less than to capture the German overseers of the Vichy administration – the German Armistice Commission - at their headquarters in the Miramar Hotel. He and his men managed to fight their way to the hotel and take all the Nazis prisoner - whereupon they waited for the American General Staff, which they knew intended to use the hotel as Patton’s headquarters. After the senior officers had moved into their rooms, Sergeant Caldwell was put in charge of security.

I was commanding officer in the HQ and my unit was designated to guard General Patton. My twenty-something men were all still soaking wet from being overturned – and brutally cold, since it was November 8th. So I left them inside the hotel as an inner perimeter of defense as I checked with the other Sergeants of the Guard. Having come afterwards, they had their units camped outside against the hotel’s walls – and had guards out, which together with my men inside seemed sufficient. But then General Patton came down the stairs with his pearl-handled revolvers and looked around the lobby at my wet men in their battle fatigues and roared, “What are these men doing inside here? Who is the First Sergeant of the Guard?”

Somebody answered, “Caldwell.”

“Get him over here!” Patton yelled.

I went forward, and Patton gave me a tongue-lashing like you can’t believe - using every obscenity for a couple of minutes or more – and telling me to get my filthy men the hell out of the lobby. Even though they’d end up freezing, I had to put the men out at once. The next day I was relieved by another sergeant of the guard and unit, and we went off looking for a place to stay.

But more German subs got in among our ships that night. Lots of soldiers had been ordered back on board to help unload ammunition and our duffle-bags (each soldier had a duffle-bag), and these subs, which had missed us all the way across the Atlantic, had come in from the north right along the beach. One particularly good sub commander had gotten right into Fedala harbor and began to torpedo the ships inside, including my ship, the Tasker Bliss and another of the five troops transports that had sailed down the coast of South America.

Lots and lots of troops and sailors were killed. We weren’t told how many until much later. The ammunition that was still on board, which was most of it, exploded. I remember the ships burning in the dark and survivors trying to get to shore and trying to get to a few of them. On top of that, most of us lost everything personal – things like my Leica.

Speaking of cameras, before leaving the Fedala headquarters, the top American and French commanders suddenly decided to memorialize their victory with a group photograph. Patton, a former Vichy general and some other big shot all simultaneously thrust their cameras into Bob’s arms, as they formed a line-up. Nothing was automatic about such devices in those days, so my Dad remembered having to fumble them all, as he figured out the settings for each one on the fly, with his gaggle of impatient masters holding their pose.

Next, my father and his unit were ordered south to Casablanca, where there was an O.S.S. vice-consul, who had been down there all along, conspiring with the head of the Vichy security police. Bob went in to establish relations with this resident American and the French police, many of whom had rallied to the Allied cause - after the battle. During Bob’s first visit to their headquarters, he was shocked to see prisoners who had obviously been tortured to “extract” information that the turncoat administrators now wanted to use to ingratiate themselves with the Americans. When my father expressed his repugnance and disapproval of such immoral and ineffective methods, his interlocutors, who felt they were on their own turf, dismissed him as naïve. Even after years in the CIA and his own country’s adoption of cruel practices after 9/11, my Dad continued to believe that torture was unreliable and fundamentally wrong – and died, as it were, both knowing all too much and utterly “naïve”.

His condemnation of such police methods may have contributed to his next assignment, which was a kind of banishment with a small unit to the frontier between French and Spanish Morocco. He was given an apartment by the French Border Police above one of their customs posts on the frontier itself and spent almost a year away from the fighting, having adventures in the desert. Bob was actually, theoretically, in charge of securing the entire perimeter of Morocco and had people under his command who were so far away across barren deserts and snowy mountain ranges that easy communication with many of them was impractical, if not impossible. One agent was

“up in Oujda, which was in the eastern part of Morocco, and a couple of other places along the border – Souk el Arba, for example. That was where I encountered Patton for the last time before fighting under him again in Europe. I had been asked to set up a boar hunt for him. So I made friends with the local tribal chieftain, Sheik Tali Al-Al, and we got his Berber tribesmen to form a beat to scare the boars through the brush so the general and his people could shoot them. Then I took the general to the farmhouse that the sheik had provided. As we got there in the dark, someone told Patton that his son-in-law was missing in action and presumed killed – I think near Sidi-Bou-Zid in Tunisia. Although Patton had this reputation as a ruthless hard-ass, he was extremely emotional, and as I stood there watching him, he sat huddled over, weeping hard.”

One of the adventures Bob had during this fairly enjoyable interlude between battles prepared him for his first major posting as an intelligence officer after the war: “I played hooky and went up to the international city of Tangiers. It was supposedly off-limits, but I made a lot of good friends with both the American and British diplomats going through – and learned a lot that was helpful after the war.” It was 1944 and the Allies were about to attempt their first landing in Europe. Bob and his unit moved first to Algiers, then to the staging base at Oran, where they boarded another troopship.

On the eve of his second landing, the darkened invasion fleet passed Stromboli as it erupted in the night, with red lava bleeding down its flanks and cinders showering into the sea. Thousands of men going into battle watched spellbound – until dawn, when they hove to before Naples with Vesuvius smoking in the distance. Whenever he found a lump of pumice washed up on a beach, Bob would think of that night.

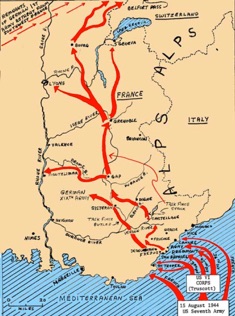

This landing was much smoother, and Bob’s unit began working its way all the way north to Florence. Like the sinking of the Normandie, the purposeful mining and destruction of the neighborhoods on either side of the Ponte Vecchio in Florence by the retreating Nazis seemed like an insult to humanity’s fitful efforts at creation. After witnessing this vandalism, Bob’s unit was summoned back to Naples, where the army was staging for the invasion of southern France. My father was attached to the headquarters of the youngest commander of ground forces in the theater, General Fredericks, who led the 1st Airborne Task Force.

Attacking by glider or parachute was all the unit did. The Germans forced their laborers to erect rows of tall poles wherever they thought the “black riders” might come in, in an effort to mangle the gliders and kill their occupants. It was safer to parachute, but parachutists often fell off target. All the people going in on gliders had already been assigned and there wasn’t enough time to train Bob to be a parachutist, so on D-Day, in August 1944, he and the terrestrial contingent of the First Airborne sailed in darkness between Sardinia and Corsica towards St. Tropez, landing just to the west at Cavalaire-sur-Mer. Once the airborne forces found each other, they began to drive the Nazis east towards Italy. In the meantime, my father took a small detachment to St. Tropez and remembered the rest like this:

I think there were only four in my group. At night, German Reconnaissance planes and Fighter Bomber squadrons would fly over our fleet, which was anchored just offshore - and every one of our anti-aircraft guns would open up. It was just a great display as ack-ack fire went every which way. So much shrapnel was bound to fall from the sky, that it seemed prudent to get down and inside somewhere. But the commander of our unit, Captain Marian Porter, stayed out to watch the show and got seriously wounded by a piece of falling metal. As a tech sergeant, I was the next guy on the totem pole, so I got a combat promotion to lieutenant - not for great acts of heroism but just for being prudent and staying out of the way. Captain Porter, who had been in charge of C.I.C., stuck his head out when I stuck my head down – and I got my battlefield commission, becoming an officer and a gentleman.

One of the American vessels at anchor. Photo taken by Robert Caldwell in 1944.

Part of my father’s wryness about rank derived from his own father’s wry observations about class pretensions, but it was also based on my Dad’s work as a spy-catcher. Unlike anyone else in the US military, C.I.C. agents just wore “U.S.” on their collars, so they could have jurisdiction even over a general if it became necessary for counter-intelligence purposes.

While engaged in a host of violent and significant missions, Bob was also drawn into the military’s daily life. The two biggest hotels in Cannes were the Caravelle and its neighbor, the Carlton. There was a race to requisition such hotels – or at least their linen and other furnishings – between the army, which was landing but moving on, and the air force, which wanted places for R&R. Bob was suddenly drawn into this race when a Major Renz of the Air Force requisitioned the Caravelle only to find that the army had not given it up gracefully, but had taken all the linen and other comforts. The French hoteliers were in despair. Strangely, in the real world of the battlefield, members of different branches of the military seem to have relied occasionally on C.I.C. agents, who were seen as being slightly outside the military’s rigid systems, to act as ombudsmen.

So it came to pass that Bob intervened in the linen caper and retrieved all the Caravelle’s belongings – to the great gratitude of Major Renz and the hotel staff. They announced that he would always have a room, if he ever came back. Long after the war, when Bob found himself forced to pay for his own room in the very same hotel to meet his new father-in-law’s expectations, the hotelier recognized him and saved him from an expense that a junior civil servant could hardly afford.

In the meantime, the army had to move out of the steep valleys along the Riviera to the more open passage north along the Rhone. At one point the only road for the army snaked along the bottom of a narrow valley with the Nazis on a ridge above it, blasting the American column below, and competing factions of French resistance fighters shooting at each other from opposite slopes, over the army struggling to advance beneath them. The local commander of the Communist faction - rather than the one that pled allegiance to de Gaulle - took Bob to his well-stocked arsenal to prove how well prepared his fighters were for the coming annihilation of his Gaullist enemies and insisted that the Americans should only back the Communists to be sure of leaving allies in their wake, who could be counted on to protect their supply lines. The quantity and quality of his faction’s weaponry was astonishing - stacked high and thick to the rafters – and the arms were so pristine that they had obviously been saved for something more important than fighting the Nazis. Together, the implicit threat by men endangering the Allied advance and demand for favor were so outrageous that my father exploded – threatening to turn American guns on both camps unless they stopped shooting and mortaring one another until the army passed.

The out-numbered Gaullists were all too willing to comply, but the better-armed Communists stopped begrudgingly. Their presumption of righteousness and power ended up leaving the same bitter taste in Bob’s mouth that he had first felt as a seasick hostage on board the commandeered liner off Portugal.

Next came the Rhone – where I, Bob’s son, inadvertently learned of a battle among many when I took my Dad to see the Baume des Anges, one of the caves I’d explored in a ragged cliff that plunges directly into the river. Upon seeing the scarp as a man in his seventies, my father remembered accompanying infantry up that very slope to silence German artillery posts on top. Nothing more. Nothing less.

He explained that back then, in 1944, he had joined an ad-hoc armored force called Task Force Butler and crossed the Rhone River to bottle up two German Panzer Grenadier Armored Infantry divisions near Montilimar. The American air force had been strafing the divisions and knocked out most of their tanks so they eventually surrendered.

At which point, Bob was sent back to General Fredericks, with whom he had grown close, and was put in charge of C.I.C. operations from Monte Carlo to the still hostile Italian frontier. Fredericks told Bob that he was frustrated because he wasn’t being allowed to move his forces across the border. He thought he could probably have gone as far as Milan, but a higher ranking general, with a third star, who was already in Italy and slowly fighting his way north, had been promised the territory. So Fredericks had to arbitrarily stop his advance, and allow his forces to be shelled by the Germans from their sanctuary on the sacrosanct Italian side of the border.

Robert Caldwell on the Riviera in 1944.

Roger had a fairly large technical unit to triangulate on radio signals and find their location. The contingent was extremely effective down there. So the code-breakers back in England who doled out information to people on the ground who might be able to do something about it - I think they were called the A-Force - gave Roger a lead on a German spy who was transmitting information on our forces. They didn’t know his name but knew approximately where he was. Roger passed it on to Rick Sickler, who had been a major by his own account in the Spanish Civil War on the anti-Fascist Republican side – and had views which were close to being Communist. This became problematic for him after the war.

Anyway, the X-2 managed to triangulate the signal and determine who the guy probably was. He was living in a house owned by James Thurber, the cartoonist. As the only person with arresting powers, I had to be there whenever we made an arrest and tried to turn an enemy spy around as a double agent, so Rick and I went to Thurber’s house. But our suspect, who was a minor French military officer, had gone off to a manor north of Cannes. Rick and I drove there in a Jeep and as we pulled up into the incredibly long driveway of this place, which may have been called Le Chateau, this young man is sauntering down the drive in his shorts. Rick just said, “Where is it?” and the guy simply answered, “Upstairs”, and, sure enough, there was his radio all set for communication and we sat him right there and interrogated him about what his danger call signs were – in case he tried to alert the Germans – we found out what those were, all the things he had to do to authenticate that he was still free – and we got him to send back.

Then we brought him back to our HQ. I can’t remember what we did with his family. He had a wife; I can’t remember children, but anyway. We sent word for a specialist to be brought in – and one was flown in immediately. We had our “double” feeding misinformation to the Germans by the next day. Later, two guys even came from A-Force to run him, and played him back for the rest of the war, although he became less important to the Nazis as we approached the Rhine.

There were other adventures. Bob even became military governor of Monte Carlo for two weeks – and was introduced by the main casino owner to his ravishing daughter - apparently in the hopes of nuptials. One of Bob’s X-2 colleagues was John Philip Marquand, Jr. who wrote novels like his more famous father. Bob recalled “trusting him with one of my girlfriends - a wonderful Australian gal - when I went off on one of my expeditions into the hinterland. I think John never got married and have a feeling he may have been gay.”

A photo of Robert Caldwell marked: “C.I.C. screening.”

But before the army moved on, another incident marked Bob far more than such brief possibilities for romance. He and Rick learned that a high level Nazi infiltrator had holed up in a particular maid’s room high in an apartment building. After climbing many floors before dawn, they tried turning the concierge’s key silently in the lock – whereupon sub-machine-gun fire shattered the door and nearly killed them both. They caught the prisoner climbing out the window.

The First Airborne Task Force was now released from limbo – only to travel north to be absorbed into the American forces fighting in Alsace. Bob was transferred to the Twelfth Armored Division where he stayed until the end of the war, returning as a 1st lieutenant and Assistant G-2 – the Division’s counter-intelligence chief.

Bob waking up beside his Jeep, 1944.

As the number of prisoners, supposed defectors and refugees grew, so did the need to screen them for information and potential risks. An incident that was palatable for us even as children was his tale of one interrogation where a suspect escaped by leaping from a second-story window in a cascade of flowerpots.

I did quite a bit of CI, but as it was an armored division, we moved fast sometimes, and it was hard to do anything long-term. All the same, I arrested a number of Nazi agents who were crossing into American lines to get information back to the Germans. We went along the Rhine to Colmar, which was shelled by huge railroad guns across the river. Then we went back to stop Siegfried Rasp’s Nineteenth Army during the Battle of the Bulge. We had to stop a big German Panzer Grenadier division coming across on a submerged pontoon bridge that they had put up rather skillfully. They came across and set up their 88-millimeter guns, and my combat commander was relieved of his duties because he did not want to attack these Germans behind these railroad tracks with 88-millimeter guns all pointing across the snowfields at our tanks. We had already been driven back. After they got rid of him, the top brass got their way and forced us to try to knock out the German guns. Our tanks were mis-positioned on a ridge and were perfectly silhouetted for the enemy against each other’s fires, making them sitting ducks. The result was that we lost 90 out of our 110 tanks. It was ghastly seeing our boys burning up in them.

The 12th Armored Division on the road.

Soldiers of the 12th Armored Division fighting in snow near Herrlisheim in Jan. 1945

We went into a rest area somewhere around Alsace Lorraine to wait for reinforcements and new tanks. The ones we got this time were much improved - Shermans with 90-mm cannon, instead of the old 75-mm guns. Then we did some fighting, but mainly followed other units through the old Maginot Line and on through the Siegfried Line into Luxembourg and finally went off from there to cross the Palatinate to the Rhine – all very quickly. There I saw Patton again, but I didn’t actually witness his famous interchange with the commanding officers of his divisions in the 7th Army. Here’s how some of its participants reported it: “How long did it take you to get there?” Patton would ask each general. And each of them would say something like, “Three and a half days” or whatever it was. “And how many men did you lose?” Patton would demand. My commanding officer, General Roderick Allen, answered “350” or thereabouts, and General Patton barked, “You should have lost more and gotten there sooner!”

Allen thought it was our greatest battle, and knew the Twelfth Armored Division had done a great job of getting past the German army and pushing them back all the way to the Rhine. He was so upset at being chewed out over his greatest accomplishment that he never got over it. Then a few days later, when our forces had all collected there, we went off into central Germany and then south and captured the first bridge that was captured intact over the Danube.

On the way, the Division passed through Heidenheim an der Brenz, in Bavaria – where all the 88-mm guns that had killed so many people in American armored divisions had been built – and my father discovered that the factory had never been bombed. His shock and outrage only deepened when “the newly arrived American civil affairs administrator proudly told me how he had managed to finagle the war-long ban on bombing the area so the headquarters he had selected for himself could be preserved. He moved into that place just as planned, and then had an affair with the daughter of the Voith factories that had produced all those guns that did us in and had been killing people since the Spanish Civil War. Not one bomb ever fell on that place. You wonder about what happened back in Washington! He was loathsome. Ugh! I forget his name.”

In passing, I would like to point out that my father became a longtime victim of another conspiracy at this time – that of the tobacco industry, which was seeding its future profits by giving cigarettes to the troops. After having gone through so much, amid so many times of grief, stress and boredom, my father finally began smoking while sitting for endless hours in the back of trucks backed up along the Danube. The malignant habit would stick with him through his future wife’s cancer to a far-off day when he would have to decide if he meant to live or die. He won his final years by making one of the hardest, but most warranted decisions he ever made.

From the time Dad had joined the Twelfth Armored Division in northern France, his driver and fellow agent had been Leon Liebgold. Dad seems to have first set eyes on Leon on a troopship. Young men were playing endless card games amid the crowded bunks for cash that might become worthless upon death or confetti during a spree, but Leon resisted their endless needling to join in. The more he resisted, the more they teased and insulted him. He finally caved in. “Okay, guys, gimme the cards,” he said, “I’ll show you why I won’t play with you and you sure don’t want to play with me.” Then he shuffled the decks so fast and displayed such invisible mastery of a cardsharp’s tricks, that the audience was awed by the narrowness of their escape. “I can make cards do whatever I want,” he said, “and, knowing what I know, I can’t help myself. That’s why I won’t play with you.” No one ever insisted again. Leon had been a gambler in New York, and, after the war, tried to get his old buddy to invest with him in exporting used cars to China in the teeth of the Maoist advance. The most stirring and long-imagined reunion with a war buddy which my father ever had – perhaps even the only one - was his meeting with Leon in the early 80s, when he sought Leon out and discovered that his friend had become an illustrious actor in Yiddish films and theater.

One day, between Colmar and Strasbourg, my father’s Jeep – with Leon at the wheel - was in a column of vehicles when a plane unlike anything they’d ever seen fell out of the sky so fast, strafing its victims and wreaking such havoc – that Bob and Leon barely had time to dive into drainage ditches on opposite sides of the road. “When we crawled back together,” my father recalled amazedly, Leon said grinning, “You just deserted your troops!”

Germany had just unleashed the last of its wonder weapons, the first jets. They were too few and too late, but were still so terrifyingly effective that a hundred more might have changed the course of the war.

On another occasion, as the army crossed the Palatinate, Bob and Leon were sent to scout for a safe place to put the headquarters the next day, and were on their way back through a little village in an area that had been cleared of enemy forces, when a machine gun opened fire unexpectedly. This time both Leon and Bob dove into the same shallow ditch. “Tracer fire hit the sides, inches over our heads. We were pretty sure it couldn’t be Germans. Then someone yelled, “Cease fire!” – in English. The guys who had almost killed us were light armored troops who’d just arrived from the US - and they thought they were killing Germans, only it was just Leon and I. One of their jeeps cautiously approached and took us down into the village. This was about the closest I came to getting killed.”

Another time, Bob and his buddy were driving through an Austrian town, when they came across a squad of American soldiers who had formed a firing squad in front of a terrified man. The Americans had found a Nazi uniform in his cupboards. The suit was just the parade uniform of a municipal official but the soldiers were too revved up to believe that the man was innocuous. So Dad and Leon had to change tact.

Soldiers from Bob’s Division taking a Nazi prisoner.

Dad told the squad sergeant that he was only too right: he'd caught such an important Nazi that the whole squad would be court-martialed if they shot the war criminal before he was interrogated. Dad and Leon would have to take him to their “prisoner cage” up the road. Grudgingly, the platoon backed down and allowed the two counter-intelligence operatives to force the official at gunpoint to sit on the front of their Jeep. Then Dad and Leon roared out of town, told their prisoner to hop off, and left him agape as they simply advised him to avoid going home till the army moved on.

Photograph taken by Bob of the son of a suspect as Bob was waiting to arrest the boy’s father. Heidelberg, 1945.

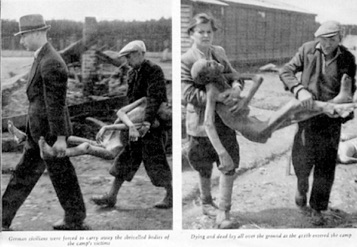

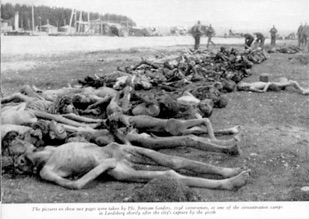

That anecdote resonates with another one. In the next memory, the army overran the Landsberg Concentration Camp Complex – six feeder camps for Auschwitz - as the Americans were racing towards their face off with the Russians. Among Landsberg’s other horrors, the Nazi guards had purposefully incinerated many of the prisoners as they lay starved but still barely alive in their bunks in the last days of the war. A young French-speaking intelligence officer like Dad no longer seemed so necessary as the war wound to a close in German-speaking territory, so he was left behind with a platoon and orders both to feed the few thousand inmates who were still - precariously - alive and to catch the fugitive guards. With tears in their eyes, many American infantrymen threw their K-rations to the skeletal survivors as the regiments were ordered to advance. Then the army and its supply train moved on, leaving Dad and his contingent to requisition food from their surroundings – even though he and his medics soon found that some survivors could no longer ingest anything, including water, but could only be fed intravenously. When fed otherwise, they literally died in their liberators’ arms.

So Dad was forced to ask the mayor of the nearest town - which overlooked the camp - for both food and supplies. Ironically, the official met Dad in full Nazi regalia and answered his requests with a diatribe about how all the supposed death camps were figments of Anglo-American propaganda. The wonder of it was that this camp's horrors were visible from the mayor's town!

Dad exploded - drawing his gun this time in fury - and marched the craven mayor downhill through the populace to see the slaughter in mass graves. The man trembled before the hecatomb, certain he was about to be added to the heaps of cadavers - and, sobbing with apparent remorse, offered the full cooperation of the town. It was a measure of Dad's generosity and lack of cynicism that he always believed that the mayor had then thrown himself into helping the survivors out of penitence.

Photos taken after the liberation of the Landsberg Concentration Camp Complex showing German townspeople being forced to face the horror. From “Report After Action: The Story of the 103D Infantry Division,” pp. 131-135

Before moving on, the 411th Infantry Regiment compelled local Germans to lay out the corpses of the purposefully starved internees - so that the bodies could be identified, if at all possible under the lamentable exigencies of the advance, and to be given proper burial.

In the midst of all this, Bob was in charge of catching the ordinary but irredeemable monsters who had even marched any internees who could still walk away into Austria in a last effort to extend and hide the magnitude of their crimes. It was a mark of his humanity that he dwelt on their victims, never on the posturings of such scum.

But my point about Dad's dedication to helping this world’s victims and underdogs would be lost if we stopped with acts of conviction because he was far too honest to cover up qualms about his own and indeed human nature. Once he wondered at the moral fatigue that had set in among the liberating troops - as they moved forward week after week through tens and hundreds of thousands of concentration camp survivors, former slave laborers and other refugees marching piteously the other way. How could he and his fellow soldiers have become so unsympathetic? That callousness haunted him.

Despite Patton’s push to take on the Russians now, the war was over. Dad finally got his orders to join a convoy down to Marseilles, where he took his Foreign Service Exam before taking a troopship home. This time he went as an officer, and since such men got better quarters, the voyage was nothing like his others. But the docks in Hoboken were empty. The youngest freshest troops, who had only recently arrived in Europe, had been the first ones to be sent home, because the army thought they might be needed to invade Japan. So, ironically, it was the rookies who were received with dockside bands, confetti and parades.

The soldiers who had served the longest – like my Dad - were repatriated later. So, when he and the other battle-worn veterans finally got back, there was nobody to greet them. “The country had gotten over the war. By that time, we had dropped our bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and nobody was interested in soldiers who had been over there for years, in my case actually from the beginning to the end.”

Years later, a fire in the army’s archives in Saint Louis destroyed the records of thousands of enlisted men, including my father’s and made it almost impossible for him to fight another bureaucracy, which, in the absence of its own records, came to deny that he had even served so long or risen to such a high rank. Luckily, in the midst of battle, he had kept copies of all his orders and records, but died ineligible for social security because of his lost years.

Part II will tell the story of the years when he and my mother formed a family, gave us our lives, and placed the world before our eyes. Until I write it, I cannot convey how grateful I am for those gifts.

A taste of better things to come…

Robert during flight training at Montgomery Field in 1946.

Roo and Bob Caldwell on their wedding day in 1951.

Robert & Maureen in Old Acquaintances, ca. 1948 in Tangier with Tennessee Williams, Paul Bowles and Truman Capote

Ruth and Robert Caldwell on South Beach in the early 1950s

The author, Duncan Caldwell, at the Pyramids. Christmas, 1953.

Edward Caldwell, Susanna Caldwell/Linfield, little David, and Jennifer Caldwell

Bob hamming it up with a Yemeni and his jambiah dagger, Beit Bawz, Yemen

Eulogy for my father Robert Granville Caldwell, Jr.

Here’s the ugly fact.

In a beautiful setting.

As horrible as its consequences were, the stroke that finally contributed to ending my father’s life left my Dad in a state of limbo: a terrible grace period which allowed all of us children to be with him one last time. I must not dwell on certain things, caressing his brow in parting, for example, or I will never get through this. But I’d like to tell you about some of his final utterances, which were among his shortest and pithiest, because of partial paralysis.

His caregivers were tremendously giving of themselves, but, in the need to be so routinely upbeat, overused such words as ”awesome”. As one who did homework under my Dad’s guidance, I know what a stickler he could be about language. He would even re-write his colleagues’ cables from Saigon when carelessness might lead policy-makers far from the field to misjudgments, perhaps even war. But the policy makers ignored both clear analysis and good advice and later blundered in anyway.

At a more personal level, my father knew from self experience that speaking before thinking – and by that he meant deep decisive thinking - leads to words which can come back to bite one. So here’s this old stickler for linguistic precision being eased awkwardly around a corner by caregivers, and one of them says encouragingly: “That was great, Bob. How are you feeling?”

He spelled it out for them: “Aaahe! dub-uh! eee! esS! OOO! eM! EEE!” - “awesome”.

His caregivers couldn’t make head or tale of his croakings and cast glances at each other – it was obviously dementia. But his deadpan parody of one of their upbeat words actually showed that his personality was clear and intact. He could be irreverent, iconoclastic, even curmudgeonly - some thought – but words, the tools of our beings, were important.

*

Another time, even closer to the end, when Dad was so helpless and tethered by tubes and straps that one might have thought that he no longer had any control over his life, he managed, out of nowhere, to ask himself aloud: “I wonder whether I’m doing the right thing?”

This was the guiding question of his life.

His life – as you will see when you read the short biography that we’d like you to pick up back at Bob and Roo’s house – was so momentous in incidents that cast light deep into 20th century history that he often had to make daunting ethical decisions. As many of you know, he had a somewhat shy and ironic perspective on life - often just watching, and, if caught, wiggled his ears.

During the war, his perspective was even more unusual. First, because he was one of the first to arrive and last to leave the combined African/European theaters. Secondly, because he started as a private and fought through three landings and four campaigns but was always attached to headquarters – seeing the whole war from both top and bottom. And, three, because he was a spy-catcher who wore no rank on his collar, just the letters “U.S.” – in case he ever needed to arrest a general.

This suited his egalitarian nature. And his priorities.

- First, he was an American patriot – who sought to protect this country both from its external enemies and xenophobes, racists and other impulsive men who carry their jingoism at the end of a gun.

- Two, he was circumspect about authority, and cherished a system built on grassroots politics, balances and dissent. In fact, he thought many countries with oppressive systems could improve their governance immeasurably by simply studying the bottom-up politics and news reporting of his beloved island.

Now, as his body failed, that basic question - “I wonder whether I’m doing the right thing?” - which he had tried to answer well in so many life-or-death situations – and from day to day - again guided his thought.

Had it come time to give up existence itself? He had lived it so richly and tenaciously, over so much of the planet, that giving up went against the fiber of his being. But he answered that question with final courage, counting down the dates on the wall pad opposite his bed to the fateful anniversary of his beloved wife’s – my mother, Ruth’s - death.

**

And that was another thing he spoke about: courting Roo in the basement of the Phillips Gallery in Washington. The “Boating Party” – Renoir’s masterpiece – was given pride of place in the main galleries, while the founder’s own, relatively weak paintings were hung somewhere for decorum’s sake – in a rarely visited basement gallery. It was a place where Bob and Roo could be undisturbed for hours as they got to know each other.

And he was grateful for this ironic side effect of the owner’s pretensions. They had provided them with a sanctuary. Despite the horrors Dad saw in so many places, he found most human foibles endearing – and was usually the first to laugh at himself.

But when humans close their hearts to the consequences of their selfishness or certainties – leading sometimes as far as the horrors he had to alleviate, when he was left in charge of saving survivors at the Landsberg Concentration Camps - he was no longer indulgent. Even when the failings were his own.

***

We read to him in his moments of semi-alertness. The book was Legacy of Ashes – a scathing history of misconduct within the CIA. He had been reading it before his stroke and wanted to continue with the indictment of an institution that he had devoted much of his life to.

But the long chronicle of blundering and perversions by careerists and ideologues made us uncomfortable for both him and ourselves. Why should he suffer the ignominy of hearing this record as he lay dying? We tried changing the book. But he rallied his strength and stopped the discussion by announcing: “At this point, I might as well listen to something I know a bit about.”

With his eyes fixed in space, he would sometimes startle us with judgments upon the many knaves and few heroes in the book. I had heard these opinions before, but hearing them this time was uncanny, because the author’s hindsight tallied so closely with my father’s observations.

And then, slowly, over the weeks, it dawned on me that - despite the long chronicle of folly – Bob had never been there when others derailed the train. We had always arrived right afterwards. He had been repeatedly sent to clean up after the schemes of men blinded by procedures and certainties collided with such niceties as cultural differences. And he was chosen because he was a purist who could be trusted to rebuild by focusing on the Agency’s only true mandate: to gather intelligence – in all senses of the word.

Now, facing history’s collective judgment, with his work going down unrecognized with the soiled bath water, Dad never mentioned these facts. We knew he had taken countless steps to save lives, support democracies and end practices like torture which he felt was repugnant, unreliable, and a stain on this country’s principles. But he would not seek absolution.

****

Which brings us to why we are doing this memorial like this: without the benefit of pomp, props or religious organizers. Although Bob was so deeply circumspect about human pretensions, he found this miracle we find ourselves embedded in “Awesome” in the deepest sense of the word. So awesome that he would not presume to make it fit words or the human condition. He felt it was better for him – at least - to be simply grateful and reverent - and expect nothing in return.

So, during those final weeks, he asked us to keep it simple – he had nothing against invoking a higher being, if it made the living feel better - but he wouldn’t presume that it mattered. As always, he was clear and met even the ugliest fact squarely.

I love him for all this – and so much more - for he was truly a man of honor and courage.

Finally, I was asked what words I would leave near this beautiful stone from his favorite beach, the Brickyard, and these were the ones that came to mind:

If only one could squeeze moments

out of memory,

Roo would thrill again

to the sight of the snowy owl

and the bulbul would perch on her finger.

Gouramis, so sure of Bob's care, would nest in pearls.

And gales of laughter would reach our ears

upstairs.

Dad would climb beaches

under fire

- and the Krak's gusty parapets, holding our hands.

Our parents would woo again

in the museum's basement - and hold true

even in pain.

Such solidity, so much color, such life! Each day

phosphorescing differently before their eyes.

Drop a green stone from far shores

here where travelers are wed

with everything

they made glorious - shores of sand, shores of rock -

drop a green stone - and look around.

This is for our parents, Ruth & Robert.

Related webpages

Duncan Caldwell’s home page

Other writing by Duncan - The Foz Coa prehistoric rock art scandal

A Murder, Bombing, and Trip to “Dolmens”

Duncan Caldwell’s paintings

Duncan Caldwell’s scientific hypotheses: The prey-mother hypothesis

Baby slings & Human evolution: The baby-sling, bald-body hypothesis explaining how baby slings may have triggered the speciation at the root of our genus, Homo

The Neanderthal insulation hypothesis concerning Neanderthal diets, extinction and adaptations to glacial cold

Key Words: Second World War, World War II, counter-espionage, counter-intelligence, General George Patton, Columbus Grove, Ohio, Spanish Civil War, New Trier High School, Jim Thorpe, Andover Academy, V-12 Navy College Training Program, V12, Counter-Intelligence Corps, C.I.C., Tasker H. Bliss, General Patton, North African landings, Fedala, Jean Bart, Cruiser Brooklyn, Vichy, Office of Strategic Services, O.S.S., General Noguès, General Béthouart, French Resistance, Task Force Butler, X-2, James Thurber, Siegfried Rasp, Battle of the Bulge, Heidenheim an der Brenz, Twelfth Armored Division, Leon Liebgold, Yiddish theater, Yiddish films, Landsberg Concentration Camp Complex, 411th Infantry Regiment, Morocco,

Key Words: United States army intelligence during WW II, American World War II veterans, Second World War espionage, , U.S. Army Counterintelligence Corps, World War II Military intelligence, Robert Caldwell, Second World War, World War II, counter-espionage, counter-intelligence, General George Patton, Columbus Grove, Ohio, Spanish Civil War, New Trier High School, Jim Thorpe, Andover Academy, V-12 Navy College Training Program, V12, Counter-Intelligence Corps, C.I.C., Tasker H. Bliss, General Patton, North African landings, Fedala, Jean Bart, Cruiser Brooklyn, Vichy, Office of Strategic Services, O.S.S., General Noguès, General Béthouart, French Resistance, Task Force Butler, X-2, James Thurber, Siegfried Rasp, Battle of the Bulge, Heidenheim an der Brenz, Twelfth Armored Division, Leon Liebgold, Yiddish theater, Yiddish films, Landsberg Concentration Camp Complex, 411th Infantry Regiment, Morocco, Moroccan campaign, U.S. intelligence, World War II espionage, World War Two intelligence operations, cloak and dagger, Intelligence corps, CIC, Robert Caldwell’s biography, Leon Liebgold, Yiddish theater, Yiddish films, U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps history, World War II German spies, History of the CIC in World War II, US army intelligence, Jewish holocaust <meta name="google-site-verification" content="GyQd7B7UUPsJ9FMuzt3Y0SBafx2bjQjF_uVPtbFD7S4" />