Designed by Duncan Caldwell

The institution’s name reflects both the architecture with its spring surging from a tumulus and the underlying metaphor of renewal through the study of deep time.

I was inspired to design the complex as an intellectual exercise in drawing together the most successful aspects of museums I’d visited, while leaving out their weaknesses.

I also wanted to create a museum that would honor its subject by using a lexicon of prehistoric architectural forms found around the world, including ones drawn from tumuli, megalithic alignments, and rock shelters chosen by their prehistoric inhabitants for their waterfalls.

Another guiding purpose was to maximize building and maintenance efficiencies per square foot while similarly maximizing functionality and impact. An example of this is the galleries on the garden and top floors, which are both terraced, making the exhibition spaces intrinsically dramatic while preserving adaptability for changing displays.

Another principle that was extended to its limit was accessibility, since the museum contains no stairs, but instead relies entirely on wheelchair accessible ramps for the flow of its users.

A final goal was to create a structure and entity to which I could happily contribute my efforts for years to come, ranging from exhibition design and curatorship to prehistoric research.

But no sooner had the plans reached their first iteration than word reached an ambitiously expanding institution in North Carolina called Mount Olive College* that Dr. Richard Michael Gramly - who the college had asked for advise in creating a prehistory museum - thought the college should replace a design drawn by an architecture firm in Raleigh with the one he’d seen while visiting caves with me. He must have been incredibly persuasive, because the next thing I knew, the college was sending both its chief development officer, Chris Wood, and the project director, Dr. Daniel Gall, to see the sketches.

After studying them in detail, the delegation convinced Mount Olive’s President, Dr. Byrd, to convene a meeting of its trustees, benefactors, advisers, deans and other interested parties to choose between the two visions. This committee, which met in Feb. 2008, voted unanimously to use my design – but the college faced increasing difficulties in launching the project as the economy worsened, and then stalled. From the beginning, Mount Olive recognized that the concept and plans would remain my intellectual property until the college purchased them – and that I was free to use them elsewhere until that happens. The college’s difficulties have thus freed me to keep seeking a home and backers for my vision of an institution focused on the study of life and cultures from deep time - and their profound implications for the present.

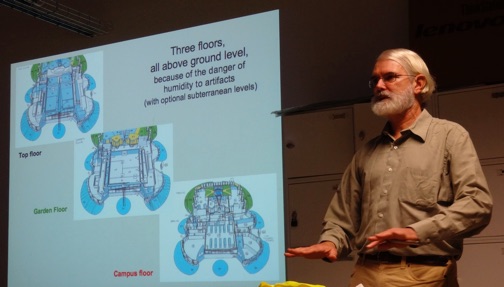

In the meantime, I was asked to delve into the details and inspiration behind the plans in a lecture for doctoral students at the École Nationale Supérieure d'Architecture in Nantes on Dec. 12, 2013 that I called “Designing Time Machines: Reflections on the creation of archaeology & ethnology museums”.

Here are some drawings from that presentation, which used the project as a departure point for considering the strengths and weaknesses of institutions around the world, and was followed by an afternoon workshop.

-

*The College changed its name to the University of Mount Olive as of January 1, 2014.

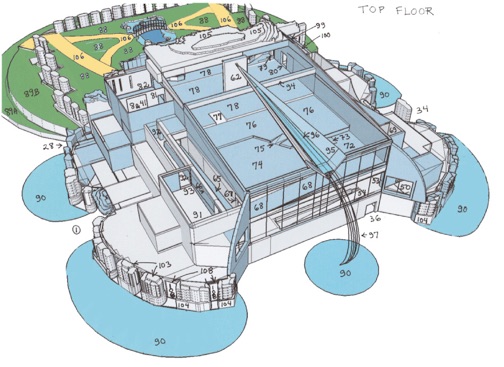

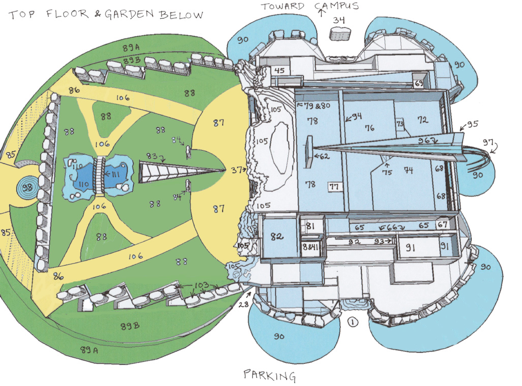

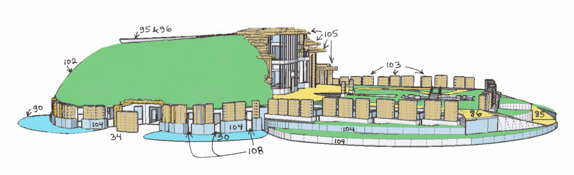

With the exception of the stream channel (95 & 96) bisecting the roof and the ledges of the “rock shelter” ((105), all other aspects of the roof, including its grassy slopes and underlying supporting structures, have been deleted from this rendering to show the terraced gallery (72-78) and other structures on the uppermost floor in the building. These include a storage room (91-92), upward ramp from the garden-floor gallery below (65), and downward ramp (accessed at 80 with a bend shown in a cut-away at 69) from the top gallery to the gift shop.

The right side shows the museum’s top floor with the terraces of the uppermost gallery rising from right to left 72-78). Sections of the “rock shelter” (105) are suspended above a reception area by the windows overlooking the garden. This reception zone is partially visible in this view as a cut away (82) but extends under the “rock” ledges marked 105. Other features of the top level include storage rooms (91), ramps (65), the service elevator & mechanical rooms (8, 41 & 81) & the roof stream (96) in its ravine skylight (95) cutting through the “turf” roof.

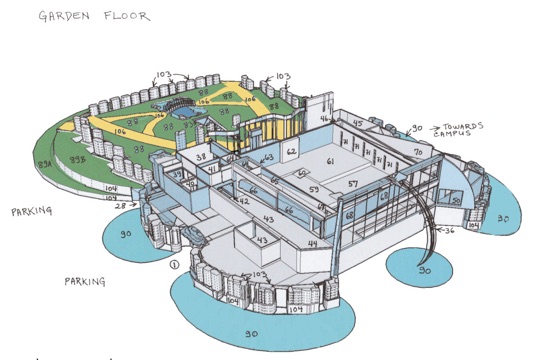

The upper gallery has been stripped from this view to show the terracing of the garden-level gallery (57-61), but the ramp from the garden-level gallery to the upper one (incorporating features 65, 66 & 67) and also down from the upper gallery to the giftshop (70) have been partially left in place to show entrance and egress.

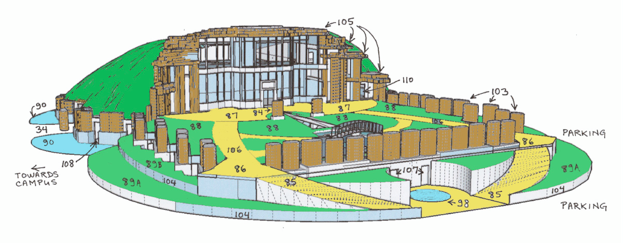

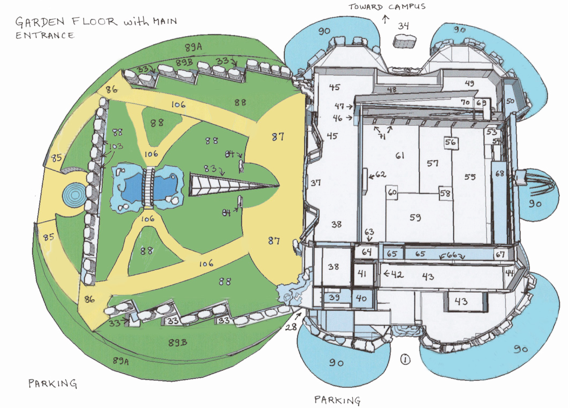

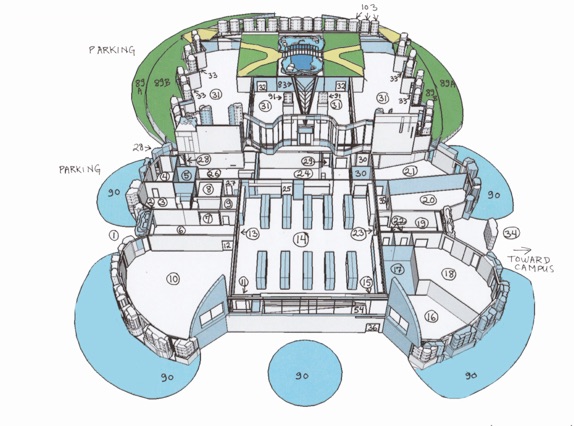

A bird’s eye view of the museum’s garden & garden-level floor showing the 2 ramps (85) up to the raised garden within its megalithic walls (103), the garden’s lawns (88), walkways (87 & 106), pond, bridge and ravine sky-light (83), the museum’s entrance hall (37) with its associated restaurant (38) & gift shop (45 & 49), and upward terracing from right to left of the gallery (53 – 60) on this level.

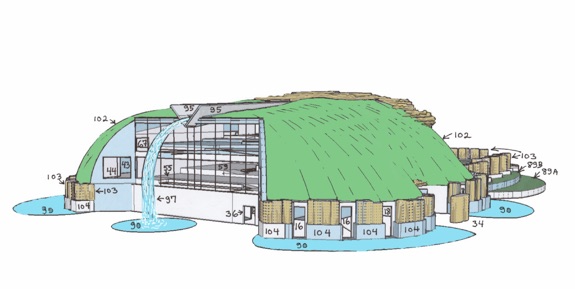

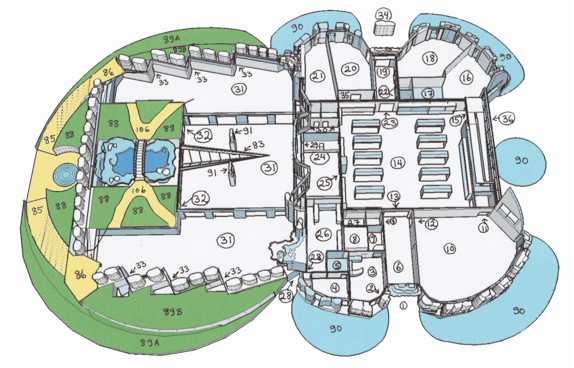

A cut-away view of the museum’s “basement” level – much of which is naturally lit and none of which lies below the regular soil surface, so as to avoid artifact conservation problems due to flooding and soil hydrology. The left half of the design shows areas under the sculpture garden (#31) which are designed to be used flexibly as labs, offices, reserves and extra exhibition galleries. The right half shows the bottom floor of the raised tumulus section of the museum. It consists of a multi-media center (16), classrooms (#18, 20 & 21), public reserves (14), a lecture hall (24), a lab (10), a visiting lecturer’s / curator’s apartment (3,4 & 5), entrance halls (6 & 19) and kitchen (26 & 27), along with ramps, restrooms & storage.

Another cut-away view of the museum’s “basement” level. The Open Reserves hall (14) contains 9 foot-tall glass cabinets that are 2 feet deep on each side (making them slightly over 4 feet across). These well-lit crystalline cabinets would be filled with a myriad objects, all bearing clear reference numbers. The purpose of this room is to show most of the pieces in the museum’s permanent collection which are not dramatically exhibited in one of the terraced galleries upstairs. While masterpieces might be shown on the upper floors, secondary pieces would be displayed here for visitors interested in the rest of each series. They could find information on any piece by typing its reference number into a keypad beside several flat screens placed on walls around the hall, or on one of the computers in the Media Center (16) opposite the bottom of the ramp from upstairs (54).

Wellspring Museum complex showing slow-growing, highly resistant Korean velvet grass, growing out of thin mats containing irrigation capillaries, over the “tumulus”.

The design for the Wellspring Museum reflects three things:

-the “spring” welling from its roof and flowing over a streambed, which doubles as a skylight illuminating a dramatically terraced gallery below,

-the cascade off the roof past gallery windows on both the top and garden floors, and,

-the mission imagined for this building by its designer, which would be to celebrate the relevance of deep time to our lives, cultures and dilemmas.

Its integrated building/landscape complex consists of 3 levels:

-the Campus Floor (Lowest Level) with its open reserves, theater, class rooms, lab & administrative spaces (Numbers 1-36). This floor has two major entrances, neither of which would usually be for the public. The entrance facing the campus would be for students, professors and administrators and is heralded by a natural stone monolith standing apart from the megalithic walls – a kind of sighting stone. The second entrance faces the parking area and is for deliveries, laboratory workers and other professionals.

-the Garden Floor with its main lobby, gift shop, café & the lower of 2 terraced galleries as well as a raised garden surrounded on three sides by megalithic walls, (Numbers 37-71). The ramps at the end of the garden and paths across it provide the main public access to the museum.

-the Top Floor with the higher of 2 terraced galleries. At its lower end, this gallery overlooks the cascade falling from the channel across the roof, with its glass bottom, which allows sunlight to filter through the stream into the room, while its upper end overlooks the megalithic garden from the craggy perspective of the rock shelter.

The Wellspring Museum would present exhibitions derived from its own holdings, such as one on the ways that “The Head” - and, by extension, the mind - has been interpreted by different cultures and artists. From the start, these holdings would include one of the most comprehensive collections of prehistoric & ethnographic works, thanks to generous offers that have been received from benefactors.

But the Wellspring Museum will simultaneously host shows of original objects from lenders. “Masterpieces from the Cradle of Europe” and “Prehistoric Venuses” are two that I have already organized using loans from important national institutions. Such shows would travel to all external venues under the museum’s aegis, giving the Wellspring Museum a larger presence in the world. One goal is to initiate such traveling shows – but to do so ever more frequently by exploring themes suggested by the museum’s own holdings. This & the extensive reserves accessible to the public in the subterranean glass cabinet room (14) will allow the museum to keep most of its collection before the public. These exhibitions and such profit centers as the gift shop, café-restaurant, reception rentals, and media sales - with great emphasis on creating attractive publications that become sought-after references and standard-bearers for the institution - will all help to maintain the institution’s financial health.

The advantages of having natural grass growing out of a “turf” roof

- First, because there are several well-established techniques for installing and maintaining grass or wildflower roofs economically. As a consequence, such roofs are becoming increasingly common (the new Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, Bercy Stadium in Paris, etc.).

The California Academy of Sciences

- Second, because a larger section of the museum – namely half the campus floor - is under a garden, so the issue of a roof of lawns and gravel will have to be addressed anyway.

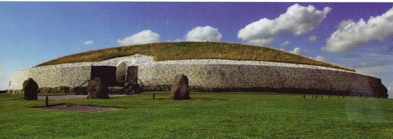

- Third, because visual allusions to the megalithic tumuli at Newgrange, Ireland, and Gavrinis in France and to mounds from prehistoric Etowah to Cahokia in the United States.

The Neolithic tumulus at Newgrange

- Fourth, because rock shelters erode out of grass hills, meaning that the rock shelter facade must jut from grassy surrounds to avoid an architectural mixed metaphor.

- Fifth, because slow-growing, even, and lush grass cultivars decrease run-off and give buildings an environmentally friendly image, which, when combined with the geothermal climatization foreseen for this museum, is becoming increasingly important. An example of such a grass is the Korean velvet grass used in modular tiles made by Toyota Roof Garden (a subsidiary of the car company). These TM9 roofing tiles are twenty inches square, about two inches thick, and the grass only needs to be cut once a year while providing excellent thermal insulation. The relative thinness of the tiles also reduces the need for designing a roof with a huge carrying capacity.

The mats are also irrigation-ready with tubes through which water automatically feeds the roots.

The price? Just $43 per square yard. Once again, here are some of the benefits of this and related technologies. Grass roofs:

-decrease the amount of runoff water from storms

-cool the interior

- emit oxygen while reducing toxins in the neighborhood

-reduce energy costs, and

-lead to longer roof life, due to the reduction of exposure to the sun in hot summer months.

© 2008 Duncan Caldwell