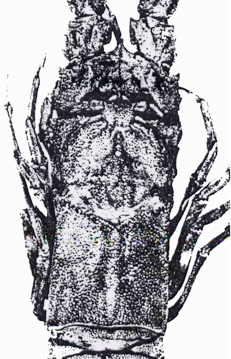

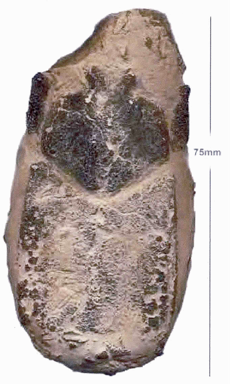

The positive side of the nodule. The specimen from Martha’s Vineyard is missing all but one segment of its abdomen. The tips of the frontal horns are 3.7 cm. apart. The lateral ridges on the carapace’s aft section are 4.5 cm. apart & the length from the bulbed rostrum to the rear of the remaining section of abdomen is 10 cm. The nodule is approximately 14.5 cm. x 11 cm.

A Possible New Species of Fossil Linuparus Lobster

from Martha’s Vineyard

By Duncan Caldwell

© 2005 Duncan Caldwell

Abstract: A new species of fossil crustacean belonging to the superfamily Palinuroidea Latreille (1803) and the family Palinuridae Latreille (1802) / Gray (1847), a family which has existed since the lower Jurassic and includes the present-day Spear or Champagne Lobster, Linuparus somniosus (Berry & George, 1972) found off Indonesia, Australia and the Andamans and Linuparus trigonus (de Haan 1841), originally identified off Japan, was found upon splitting a mud-stone nodule discovered on the bank of Squibnocket Pond in Chilmark on Martha’s Vineyard Island. Similar nodules have been found in nearby exposures of gray clay dating to the mid-Cretaceous.

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Arthropoda

Class: Crustacea

Order: Decapoda

Suborder: MACRURA REPTANTIA Bouvier, 1917

Infraorder: PALINURIDEA Latreille, 1802 / PALINURA Latreille, 1803 (Spiny Lobsters, Furry Lobsters & Slipper Lobsters)

Superfamily: PALINUROIDEA Latreille, 1802 / 1803

Family: PALINURIDAE Latreille, 1802 (Gray 1847) / PALINUROIDEA, Latreille, 1803

Subfamily: PALINURIDAE Latreille, 1802

Genus: LINUPARUS White, 1847 (=PODOCRATUS Geinitz 1850)

Subgenus:

Species: Linuparus squibnocketus

Genotype: Linuparus trigonus de Haan 1841 / Linuparus trigonus (V. Siebold) – existing species – Japan; known in Japanese as the “hakoebi” (translated from Japanese as the “sandy-mud spiny lobster”)

The genus has existed since at least the lower Cretaceous. By 1964, 27 species of Linuparus had been described. They are split among 4 sub-genera:

Linuparus linuparies White 1847

(L.) thenops Bell 1856

(L.) podocrales Schlüter 1899

(L.) eolinuparus Mertin 1941

This fossil genus is well represented in Europe and North America from the early Cretaceous of about 130 million years ago to the Eocene of about 50 million years ago. North American specimens have previously been reported from British Columbia, northern Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana and Tennessee, the northern Black Hills of South Dakota, near Dallas in Texas, and along the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal. The fossil genus is also known from Greenland, Africa and Madagascar. A single specimen of a palinurid lobster, which may be a Linuparus, has also been reported from Pliocene rocks in the Vestfold Hills in Antarctica, making it perhaps the only post-Miocene occurrence of a decapod there.

The genus is also still represented by 3 species living at depths of 80 to 350 meters in the Indian and Pacific Oceans off Africa, India and Australia, as well as in the South China Sea and around the Japanese coast. Of the 3 surviving species, L. trigonus was thought to be concentrated in Tokyo Bay, until rare catches were also reported (McNeil) from the eastern coast of Australia and the Mozambique Channel. Since then, reports from fisheries indicate that L. trigonus is more properly found from Japan to the South China Sea, while the more recently described L. somniosus is to be found from Java and Australia across the Indian Ocean.

Linuparus somniosus (Berry & George, 1972) has now been reported off southern Java, and in deeper waters off the Andamans and is sufficiently plentiful off Australia and India to be the subject of fisheries. (ie. Global Seafood Australia Ltd. & A. Raptis & Sons Pty Ltd.). L. trigonus is also available in small quantities from Taiwanese dealers during its “season” in April and May. Despite these fisheries, specimens of these species are rare over most of their ranges and the genus may be threatened with extinction.

The rostrum

The most striking specificity of the present fossil is the frontal rostrum which exhibits a single undivided bill-like projection without lateral spines that terminates in twin bulbs. It is different from the equivalent structure on all other known species. All the same, it is obviously similar to the rostrum on the existing species, L. trigonus, which also ends in twinned bulbs. In the case of L. trigonus, though, the rostrum is slightly splayed instead of having parallel sides, and bears a clear cleft down the center.

At first glance, one might think that the rostrum of the Martha’s Vineyard fossil is also prolonged by a median spine, but the spine does not really belong to it. Instead the spine turns out under magnification to be the junction of inward facing spines on the basal sections of the antennae.

Like Linuparus White, the Martha’s Vineyard fossil has two frontal horns – which in this case have a span of 3.7 cm. between the tips. Midway between each of these horns and the central rostrum, and 0.6 cm. back from the front edge, a pair of knobs also project from the carapace. Similar knobs appear in back and slightly to the side of the doubly bulbed rostrum of the L. bererensis shown below.

On the other hand, the new specimen has a dorsal crest that strongly resembles that of L. trigonus, although the Vineyard specimen’s ridge seems thinner and “sharper” than its modern relative’s counterpart. The distance between the rear ends of the lateral ridges on the carapace’s fore-section is 3.6 cm. Instead of the carapace being sub-cylindrical as in Linuparus White, it is prismatic with a well pronounced cervical furrow dividing the carapace’s 2 sub-sections. The rear section is especially box-like.

L. trigonus – Note cleft between two diverging sides of the rostrum which ends in twinned bulbs & spines.

Also tuberules on median ridge behind rostrum.

L. bererensis – Rostrum composed of 2 fully differentiated bulbs.

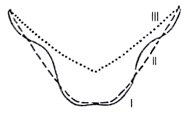

The cervical furrow of the possible new species of Linuparus

Three stages in the evolution of the cervical furrow in Linuparus.

I: Initial stage as demonstrated by L. tuberculatus Neocomian early Cretaceous.

II: Intermediary state manifested by L. bererensis Campanian late Cretaceous

III: Final state as exemplified by the living species, L. trigonus. (After S. Secretan)

It is noteworthy that the backward converging sides of the cervical furrow are intermediate between those of the earliest species as exemplified by L. tuberculatus with its sinuous lines meeting in a dimpled bulb and the far straighter lines meeting in a more prismatic bulb of such intermediary forms as L. bererensis. The bulb at the apex of the furrow of the newly discovered specimen is clearly dimpled but is proportionally much narrower than in L. tuberculatus. This archaic dimpled bulb differentiates the furrow from its latest incarnation as typified by the slightly bowed-out “V” in L. trigonus.

If the new species is accepted and its apparent combination of intermediate and modern features (dimpled cervical furrow vs. merged bulbs on the rostrum & dorsal ridge) is borne out, then the spread of this genus from Europe to America and then farther westwards to Asia and Africa may prove more likely than a dispersal from north to south via the African species found at Tanaout.

Although the fossil seems to differ from the living species in its proportions, the fossil’s state of preservation makes it difficult to compare it in further detail to modern specimens. But a preliminary comparison of the fossil to the living and fossil specimens of the genus that are known to the author indicates that the present specimen probably represents a new species, for which the name Linuparus squibnocketus is proposed. It is further hoped that the discovery of this fossil will draw renewed attention to the potential of several little known outcroppings on Martha’s Vineyard to open new windows upon New England paleontology.

Bibliography:

1)Secretan, Sylvie, 1964; Les Crustacés Décapodes du Jurassique Supérieur et du Crétacé de Madagascar – Doctoral Thesis; Editions du Muséum, Paris

2)Bishop, Gale A., and Williams, A.B. 1986a. The fossil lobster Linuparus canadensis, Carlile Shale (Cretaceous, Turonian), Black Hills. National Geographic Research 2(3): 372-387. Dr. Gale A. Bishop, Georgia Southern College, Statesboro, Georgia writing on Cretaceous Linuparus lobsters from South Dakota.

3)Lolthuis, L.B. 1991. Marine Lobsters of the World: An annotated and illustrated catalogue of species of interest to fisheries known to date. FAO Fisheries Synopsis No. 125, Vol. 13.

4)Rathbun, M.J. 1935. Fossil Crustacae of the Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plain. Geological Society of America Special Paper 2.

5)Stenzel, H.B. 1944 (issued 1945). Decapod Crustaceans from the Cretaceous of Texas. Bureau of Economic Geology, University of Texas Publication 4401.

6)Wowor, Daisy 1972. The Spear Lobster, Linuparus somniosus Berry & George, Decapoda, Palinuridae) in Indonesia; Brill Academic Publishers

7)Ludvigsen, Rolf & Beard, Graham; West Coast Fossils: A Guide to the Ancient Life of Vancouver Island which includes Linuparus lobsters found in the Cretaceous.

8)Clouter, Fred; Mitchell, Tony; Rayner, David; & Rayner, Martin 2000; London Clay Fossils of the Isle of Sheppey, Kent, UK; A Collector’s Guide to the Fossil Animals of the London Clay between Minster and Warden Point, Sheppey; Medway Lapidary and Mineral Society.

Preliminery comparisons:

1)Linuparus White sp.; Coon Creek Tongue of the Ripley Formation, McNairy County, Tennessee; Maastrichtian in age (~68 mya).

2)Linuparus grimmeri Stenzel, 1944; Eagle Ford Group, Britton Formation, Dallas County, Texas; Age: latest Cenomanian to earliest Turonian (~94-93 mya).

3)Linuparus vancouverensis; Upper Cretaceous; Haslam Formation; British Columbia, Canada.

4)L. bererensis

5)L. tuberculatus

6)L. eocenicus, early Eocene (Ypresian) clays of Sheppey

7)L. trigonus (to 47 cm. in body length – commonly 20-35 cm.)

For comparison: L. eocenicus, early Eocene (Ypresian) clays of Sheppey. Showing a fully divided forking rostrum.